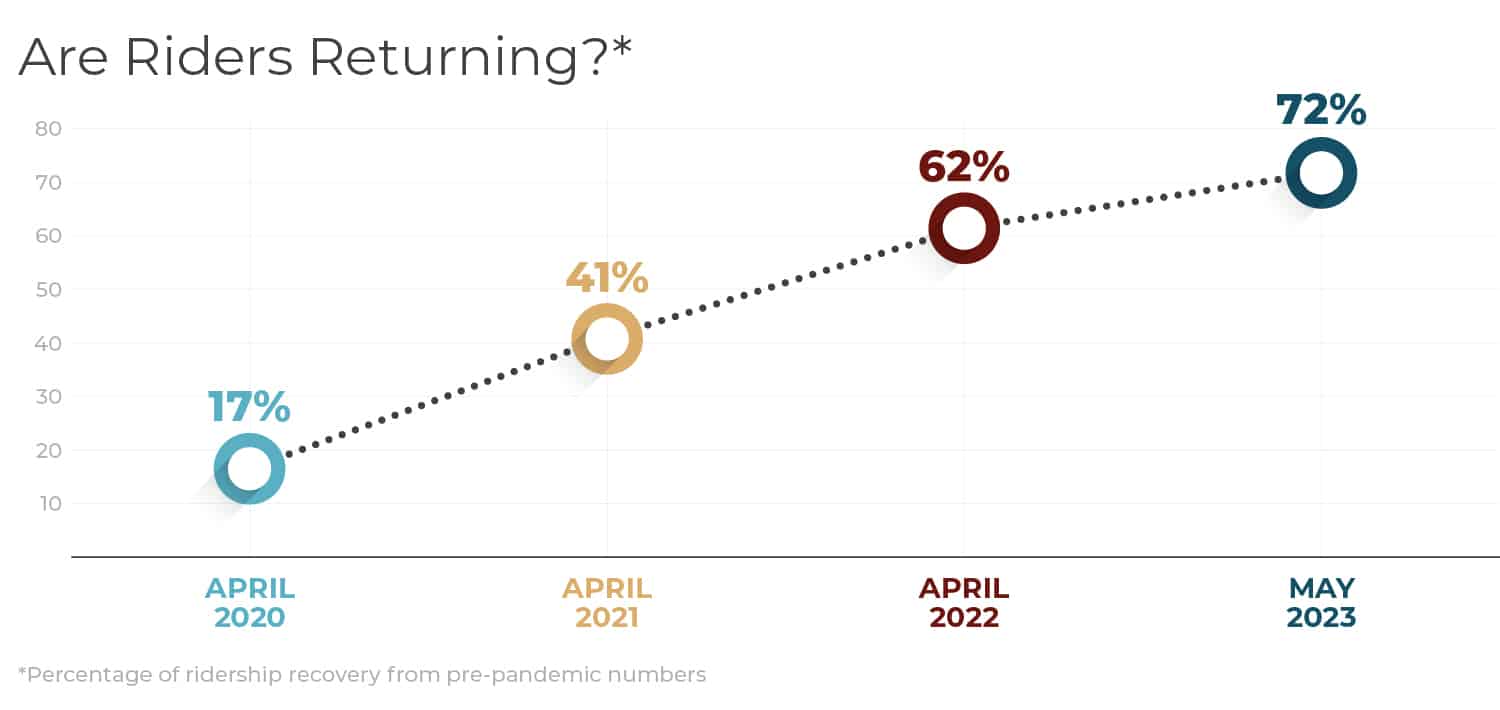

More than three years removed from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, transit agencies across the country are still grappling with a new status quo that lacks clarity. While ridership on most bus and passenger rail systems have recovered up to about 70% of pre-pandemic levels, many individuals who continue to either work from home or work a hybrid schedule, continue to do so with no clear sense of when – or if – they will return to a daily commuting schedule. Additionally, other workplace trends that emerged during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, like more scheduling flexibility, have redefined the old AM/PM peak service model, making steady, all-day service during the week and on weekends a necessity for transit agencies to continue to adequately serve the riding public.

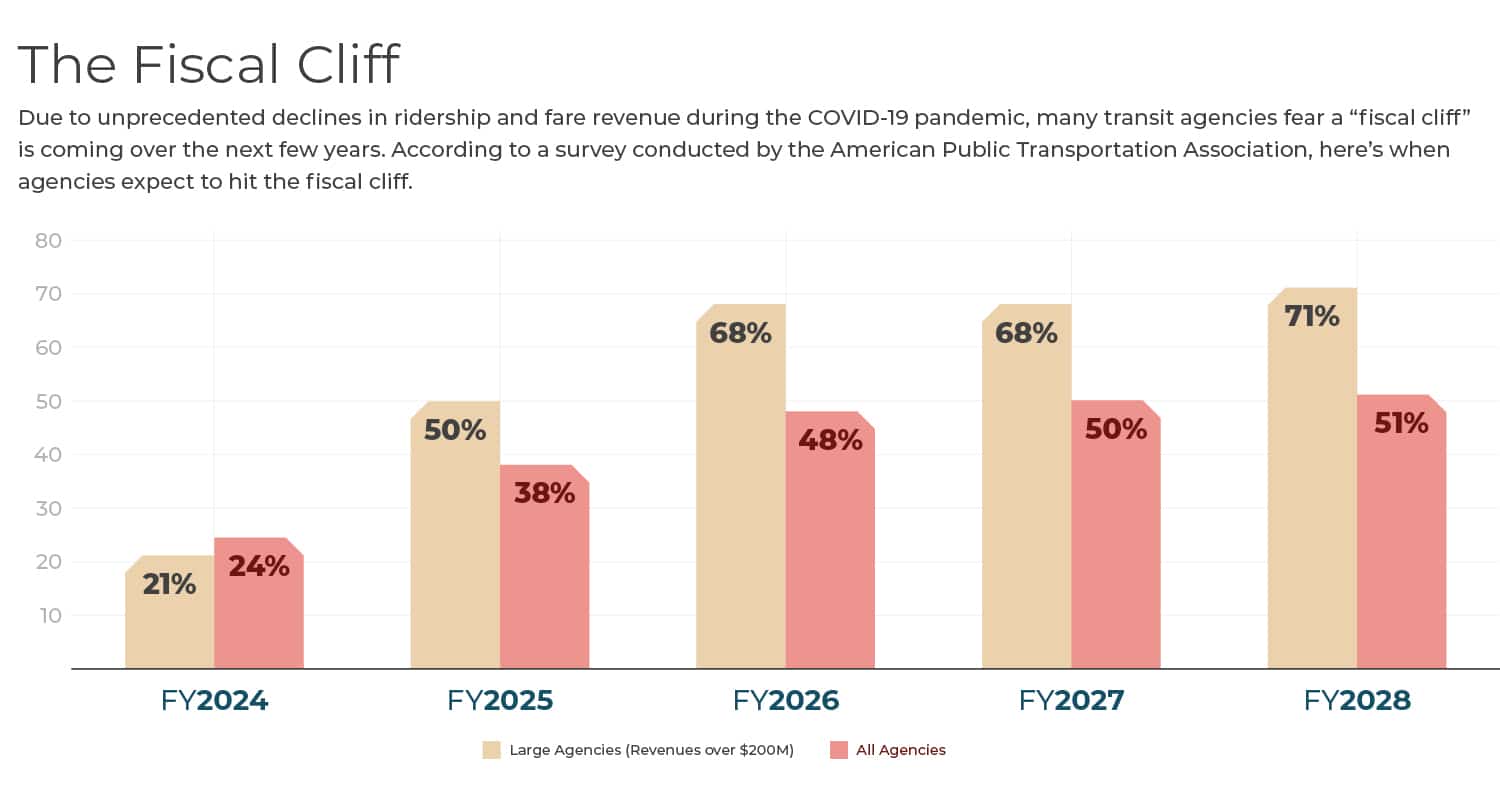

The confluence of these factors, as well as the expenditure of any remaining federal financial relief that was first distributed during the pandemic, has created a seismic shortfall in revenues for most transit agencies, with many operators fearing a looming “Fiscal Cliff” in the not-so-distant future.

For decades, STV’s team of planning experts has worked closely with transit operators from coast to coast, as well as state, local, and federal agencies to develop thoughtful solutions that have gone on to benefit communities for generations. Whether it’s supporting the earliest stages of Grand Central Madison for MTA Long Island Rail Road in New York, or analyzing ways to create more equitable bus and rail service in Los Angeles, the firm’s planning team has long had its finger on the pulse on the challenges clients are most concerned about – including the current post-COVID paradigm.

In this roundtable article, the STV team, including Phil Hanegraaf, FAICP, vice president and national planning director; Ryan Harris, AICP, planning manager; John Manzoni, AICP, planning manager; and Jason Mumford, P.E., AICP, vice president and planning manager, share their insights about current ridership trends and explain ways they’re helping clients to navigate this period of uncertainty more opportunistically.

What did we observe about transit ridership during the pandemic and how are we using this period to inform our work going forward?

Phil Hanegraaf: During and since the pandemic there has been and continues to be a struggle and redefinition of what aspirational goals transit systems should have about ridership and the services they provide. There’s been a lot of variation in terms of the level of recovery, with some bouncing back more quickly and others still trying to sort out what’s going to happen. We heard from our clients a desire to serve people who continued to rely on bus and rail during the pandemic while also trying to understand what’s next. So the question also became “How do we rebuild?” The answer to that is different across the board in terms of funding, growth in programs, and how they think strategically moving forward in the context of how they measure success and risk.

Ryan Harris: In the San Francisco Bay Area, transit agencies like AC Transit and Muni, who primarily provide local bus service in urban areas, have seen a 60-65% ridership recovery rate, which is aligned with the rest of the country. These tend to be your bread-and-butter transit riders. However, Caltrain, a rail service that connects Silicon Valley to San Francisco and carries more white-collar workers, has seen roughly a 20% recovery in ridership. These riders consist of tech workers who are still seeing a lower rate of return to the office. Similar numbers can be seen for AC Transit’s longer distance trans-bay bus routes, which have only experienced a 30% ridership recovery, again illustrating the challenge in recapturing those 9-to-5 commuters to pre-pandemic levels. As we go through the data, it’s important to pay attention to trip purpose and traveler profiles so we can help agencies understand who their core market is and how they can adjust service accordingly.

Where has ridership been the most resilient?

Jason Mumford: Based on a lot of data and discussion, we have found that ridership on backbone bus and light rail transit services has been much more resilient. Not only is this because their ridership consists of people who continued to rely on bus and rail even during the pandemic, but also due to the way land use policies were developed and implemented prior to the pandemic. We’re seeing that people who live and work in proximity to transit service are coming back more quickly, showing that it is a much better return on public investment to build and expand transit near where the people are and to encourage the expansion of transit-oriented developments.

Ryan Harris: In Brooklyn, our client made a strategic decision that bus services were vital to their riders, and that any reduction in service from pre-pandemic levels would result in a severe disruption to their core customers which would result in further ridership declines. The decision was made to weather the storm and maintain service throughout, to help the riding public continue to meet their transportation needs.

John Manzoni: In Philadelphia, ridership is still slow to return and there is an initiative to bring people back to the office that is expected to have an impact. Some employers in Center City are mandating four days in-office this fall so agencies anticipate a spike in ridership on the Monday-thru-Thursday “core days.” Meanwhile, passenger rail serving the suburbs of New Jersey into Pennsylvania/Center City, is expected to get stronger and stronger as more employers move away from work-from-home policies.

How is flexibility in service being prioritized?

John Manzoni: Rather than focus on a traditional AM/PM peak schedule, many agencies are moving to an all-day service frequency. Some of our clients believe there’s no need to have a set AM peak anymore – and that there’s no burning desire to have employees in the office by 8 a.m.

Ryan Harris: Across the board, we’ve seen a weekend recovery of rate close to 80% of pre-pandemic ridership, and in some cases, there are more weekend riders compared to pre-COVID numbers. When surveyed, commuters continually come back to prioritizing frequency and reliability. When service was cut or greatly reduced during the pandemic, many commuters urged operators to bring back frequency so that they could have the flexibility to return to transit.

John Manzoni: Several agencies even offered a monthly weekend pass because ridership was so high on Saturdays and Sundays. However, it’s unclear if now that we’re emerging out of the pandemic if the pendulum has swung the other way.

How are ridership trends from the past three years affecting project development strategies?

Jason Mumford: Clients have noticed that a higher bar has been set for them by federal agencies like the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). By that we mean, post-pandemic, the FTA appears to be doubling down on a policy that began with the Obama Administration which is to provide more federal investment to systems that are showing strong, resilient ridership. That becomes problematic for agencies that have experienced a big fall in ridership during the pandemic and are now not looking as competitive as they did prior to March 2020 when it comes to applying for federal grants.

Phil Hanegraaf: There are shifting sands related to how we evaluate projects, as we also try to anticipate what’s coming next from the federal government regarding policy and criteria. That makes our long-standing “scenario planning” approach to examining various transit alternatives as part of our analyses more important than ever.

For agencies that were planning new transit services prior to the pandemic, what has that done to their thinking and approach and how are we navigating that for them?

John Manzoni: In Southern New Jersey, where we’ve been supporting the development of the Glassboro-Camden Light Rail Transit Line (GCL). We’re unique because the service is located within a major “Meds and Eds” corridor anchored by two universities and a major healthcare establishment. While there were some questions raised during the environmental impact statement public comment period in 2021 about the need to continue investing in the GCL, a sense of normalcy is returning with every passing day, which means people are also being reminded of how frustrating it is to sit in their cars in traffic.

Ryan Harris: In areas like Arlington County, VA, which is adjacent to other transit services like the Washington Area Metropolitan Authority (WMATA), agencies are looking to increase service incrementally based on the analyses we’ve provided in order to fill in gaps that may have arisen or become more apparent as ridership by essential workers brought primary travel patterns into closer focus.

Jason Mumford: An agency like WMATA is continuing to bring back and refine its core service, but large-scale expansion programs that were planned prior to the pandemic are moving forward far less aggressively than they would have if ridership hadn’t declined so dramatically the past few years. Agencies are also pivoting toward investing more in year-over-year maintenance costs which isn’t as exciting as a “shiny new object.” However, major federal initiatives like the decarbonization of our transportation network and the rise of zero-emission transit vehicles have also presented opportunities in terms of updating maintenance facilities and garages, as well as investing in a new electric fleet.

Ryan Harris: Anecdotally, once COVID hit, people started to think transit wasn’t safe. And once people started to return to the office, there was still a level of discomfort in being in confined spaces versus being in their cars traveling to work. When investing in new transit services, agencies recognize that comfort and safety are a bigger concern now than it would have been before, and it isn’t clear how the industry responds and moves past this heightened demand.

Jason Mumford: To counter some of these concerns, agencies are looking to invest in some basic safety and security in the hope that public trust and political support of transit continues. We are seeing many agencies be more proactive in terms of having a presence of security within systems, or by having employees interact more with customers, etc. Additionally, while statistically, our crime numbers in transit systems have not gotten significantly worse when compared to the rest of the world, the loss of ridership adds to the perception that things are worse. Safety really is an existential crisis that agencies are grappling with.

What are some of the other investment and financial concerns for our clients that were brought on by the pandemic?

Phil Hanegraaf: People are concerned about an impending “fiscal cliff” where operating budgets are far outstripping incoming revenues from ridership. Our clients are very cautious about what’s going to happen to revenues and it’s creating several hard decisions as it relates to determining whether to prioritize investment in service frequency or service coverage.

Jason Mumford: With the fiscal cliff approaching, agencies are figuring out how to support lower income riders while still enforcing fare collection policies for everyone else. In one prominent rail system they have posters that let commuters know they can reach out to the agency for support if they’re having a tough time paying their monthly fares.

How are we working with clients to continue to provide the transit dependent with the access they need, while still being cognizant of overall ridership trends post-Covid?

Ryan Harris: The idea of catering to “essential workers” for transit was not one we really spoke much about prior to the pandemic.

John Manzoni: Agencies are using this time as an opportunity to experiment. Complete Streets pilot programs were implemented during the pandemic to see what impact it would have on traffic, even though the traffic never really came back. Now that traffic is returning, driving habits have adapted to the change in street makeup. For instance, in front of our Philadelphia office, SEPTA and the City painted a red bus-only lane on Market Street. It is less likely this would have happened without the shock of the pandemic.

What are some of the concerns related to leveraging data from the past three years and how are we working with transit agencies while informing their future planning?

John Manzoni: Over the last couple of years, for the projects I’m working on we used 2019 origin and destination information to project ridership. The belief there was that the effects of the pandemic on ridership would be short-lived, and things would go back to “normal,” so we’re not going to model the pandemic abnormality. However, just recently there was a new directive from FTA to use 2022 data for our baseline numbers. This will undoubtedly have a slight impact on new projects because work-based trips are still on the uprise and have not fully recovered to pre-pandemic numbers. This will cause ridership estimates to be lower compared to the 2019 data.

More broadly, the data from the past three years can prepare us as to how to handle major events in the future. From a data analysis perspective, there are a lot of positives that came out of this period. Agencies got the chance to really know what services the core of their systems are while experimenting with other elements of their system that they otherwise wouldn’t have been able to try out.