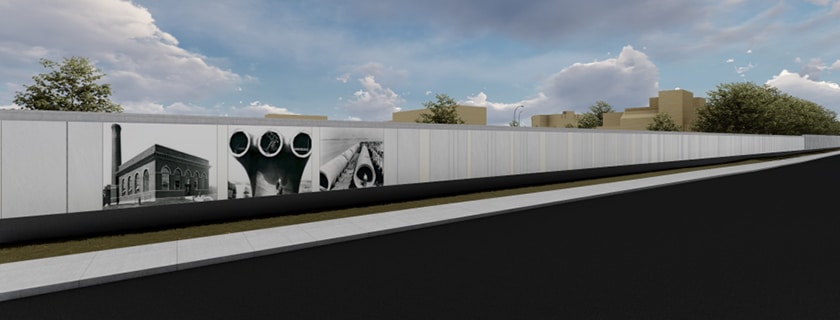

When developing the structural design for a 2.5-mile-long floodwall to protect the Passaic Valley Sewerage Commission’s (PVSC) Newark, NJ, plant – a plant that took on 200 million gallons of floodwater during Superstorm Sandy in 2012 and was inoperable for nearly 48 hours – STV’s project team was struck by how current building codes in the United States defined the impacts of floating debris on a structure.

“We were looking at the criteria outlined in both the FEMA Coastal Construction Manual and the ASCE/SEI 7 Standard, which really only considers minimum design loads for structures,” said Christopher Cerino, P.E., F.SEI, DBIA, STV vice president and director of structural engineering in New York. “In terms of debris impact, the 1,000-pound standard element correlates to a 12-inch diameter, 30-foot-long log. In an urban area like the New York-New Jersey region, debris objects can be far more substantial than a 30-foot-log. So, we thought, ‘we need to ensure that appropriate local debris elements are selected that correlate with the heightened design mean recurrence interval storm.’”

Designing “beyond the code” has long been the mantra for STV’s resilient design practice, especially in the aftermath of Superstorm Sandy, which caused billions of dollars in damages in the New York Metropolitan region, and has led many clients and stakeholders to rethink infrastructure in terms of preparedness against future disasters.

“Owners are requesting a resilient building from designers, but given the wide parameters of resilience, the possibilities of a final outcome are endless,” Cerino said. “Are we striving for a building that is operational just a few days after the maximum considered earthquake, or a facility that doesn’t take on any water following a 500-year flood in a coastal area? And without having specific guidance to this effect in our industry codes and standards, it’s on the design team to help our clients define these goals, before we can execute on a project.”

STV’s design approach for the PVSC floodwall project – which is one of several resilience initiatives the client is currently engaged with at its Newark facility that serves 1.5 million resident in the 48 municipalities of Bergen, Essex, Hudson, Union and Passaic Counties – will be addressed by Cerino, alongside the commission’s Senior Civil Engineer, Michael DeSena, at the New Jersey Water Environment Association Annual Conference on May 9.

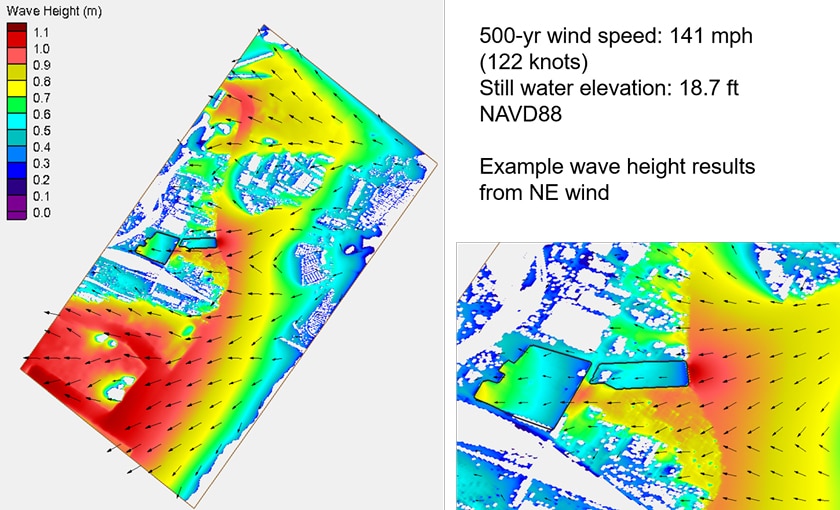

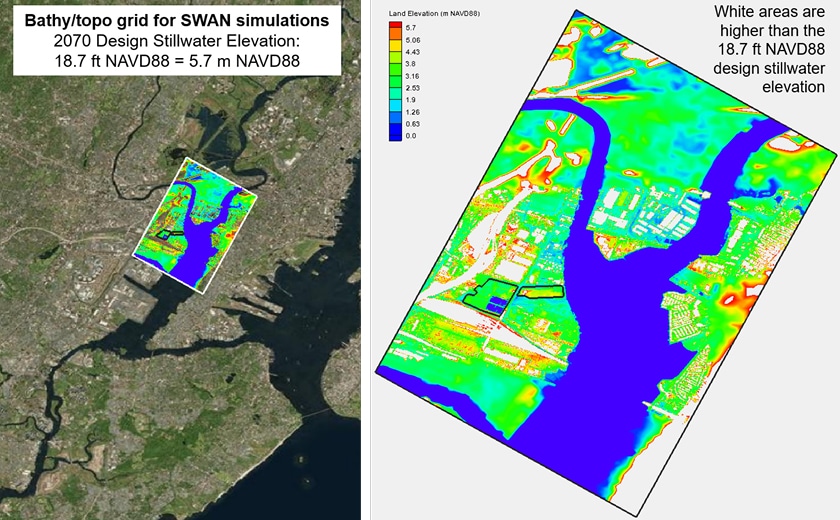

As part of this program, the STV/Mott Macdonald joint venture developed a dynamic coastal modeling system to verify where wave loads are predicted to have their highest impacts during a future storm event larger than Superstorm Sandy. From this data, the team was able to characterize the design flood, which in turn informed the systems selected for the design.

However, before the final design was submitted, the joint design team opted to look again at the project-wide design criteria considering the load impacts of possible “extraordinary debris.” Knowing the logistics of the PVSC’s Newark facility, which is adjacent to Newark Bay, the project team went beyond the code in developing a model that looked at the impacts of cargo barges – which can weigh thousands of tons with a very small draft, aka, far more than a 30-foot-long log – on the floodwall. The local barge study found that based on prevailing wind directions, there are varying degrees of barge impact vulnerabilities throughout the site.

“While we wanted to utilize the barge impact criteria in our final design, we also understood it wouldn’t be cost-effective to design a wall that had no damage after a 400,000-pound impact,” Cerino said. “To manage realistic first costs, the floodwall was designed as a dynamic mix of plastic and elastic behavior under loading. This approach will help meet the client’s performance goals which goes well beyond the bare minimum of having a facility that allows people time to exit the structure safely before a storm event.”

Visit here to learn more about STV’s Resilience and Sustainable Design practices