As more major American cities expand their transportation networks to incorporate a more dynamic mix of transit modes, the design and construction industry is increasingly turning to underground infrastructure – namely tunnels – to help facilitate service and capacity needs.

Stakeholders and project owners are finding that in many cases, underground construction is a more sustainable, efficient, economical and environmentally friendly method of creating new infrastructure systems. Additionally, many believe underground construction reduces environmental, property and visual impacts in urban as well as scenic areas, while minimizing surface disturbances.

STV’s tunneling and geotechnical engineering group has experienced a significant influx of talent over the past year, first with the hiring of Frank Pepe, P.E., senior vice president and the group’s national director, as well as the addition of several other key industry leaders who have supported the design and construction of some of the most significant tunneling and geotechnical engineering projects in the world.

In this roundtable conversation, STV’s Jim Morrison, P.E., P.Eng, vice president and engineering chief; Harshad Pandit, vice president and engineering director; Hamidreza Rezaei, P.E., vice president and national technical director of underground structures; and Barrie Roberts, vice president and tunnel engineering chief, discuss some of the current challenges facing tunneling projects today, including evolving technology, alternative delivery methodology, resilience planning, and more, while sharing their professional experience in supporting clients in navigating these issues.

Why are we seeing more owners incorporating tunneling infrastructure when it comes to developing new transit systems in urban settings?

Jim Morrison: Because that’s where the available space to build can be found. In dense urban settings, in many instances, the only place left to develop new transportation infrastructure is underground.

Harshad Pandit: From a planning perspective, traveling underground is the fastest way to commute. You don’t have to rely on surface transportation to get from point A to point B. There’s also an increasing desire to create more open spaces and parks in major cities. Underground construction facilitates the development of these open spaces, which are enjoyed by the public and bring great economic and societal benefits to communities.

What are some of the greatest technical and financial risks in urban tunneling and how have you mitigated them over the course of your career?

Barrie Roberts: A successful tunneling project starts with an investigation of the ground and groundwater to determine what some of the risks may be. We have extensive experience conducting comprehensive geotechnical investigations at the start of programs. These investigations give you a better understanding of subsurface conditions, as well as the potential impacts to any existing infrastructure that is adjacent to or intersects the project area.

Jim Morrison: A key part of engineering is solving and balancing technical and financial risks. Every project brings a new and unique set of challenges. The single biggest challenge we face is one of communication – assuring that the builder, owner, and engineer all draw the same understanding from a design. To that end, earlier in my career I served as a contributing author to a benchmark publication entitled “Geotechnical Baseline Reports for Construction,” which was published by the American Society of Civil Engineering, and commonly referred to in the industry as the “Gold Book.” The baseline report is a contractual binding document that presents definitive and common interpretations of geotechnical conditions for the development of bid pricing by contractors. It also evaluates potential changes to contract costs due to differing site conditions. This approach has been widely adopted and used in the underground construction industry for over 20 years. I am currently working with other contributing authors to prepare an update to the “Gold Book” that incorporates lessons learned and current industry practices, that is expected to be published later this year.

We are seeing more tunneling projects being procured with progressive design-build and CM/GC procurement methods versus traditional design-bid-build methods. What are the key issues that need to be considered for the implementation of these alternative delivery methods?

Barrie Roberts: Most alternative delivery methods offer scheduling benefits. The contractor is on board earlier in the process, and the design process is executed in parallel. The contractor then has input on a design that best meets their preferred means and methods which reduces cost and risk.

Harshad Pandit: Programs that are procured using alternative delivery methods, often feature innovation and outside-the-box solutions developed by the bidding teams, called alternative technical concepts (ATCs). ATCs are often implemented during the proposal and design development phases, rather than at the start of construction like in traditional delivery methods. These innovations translate to schedule and cost benefits to both the owner and the ultimate end users of the project.

What are some of the primary physical and structural challenges as it relates to urban tunneling? What are some of the solutions you have experience incorporating?

Hamidreza Rezaei: Tunneling projects in urban settings often take years to plan and design, while other development in these cities happens over a shorter timeframe. As a result, a plan or design that was first identified years earlier may no longer be feasible, leading to further modifications before the program can move forward.

Harshad Pandit: During the construction phase, there are many things we need to consider that could adversely impact a community. For example, you need to find effective ways to handle the amount of muck that comes out of the ground when tunneling, especially in a large urban setting. You also must contend with minimizing impacts from smoke and dust. On past projects, we’ve utilized innovative high-speed gantry systems to move muck quickly. To address smoke and dust during blasting operations, we’ve looked to the mining industry for solutions. On one of my past projects, we’ve utilized an air scrubber system, which is deployed after a blast and significantly eliminates dust from the exhausted air and replaces them with good quality air both underground and at the surface. Having technology and solutions like this at our disposal has helped many complex projects move forward.

What are some of the coordination and stakeholder engagement challenges you’ve encountered over the course of your career and how did you overcome them?

Harshad Pandit: It’s critical to engage with stakeholders – both businesses and residents – and bring them to the table early on. We want to listen to them, hear their ideas and help them to continue on with their daily lives with minimal impacts. Sometimes, it’s as easy as connecting them with the right solutions. In one instance on one of my projects, a local city restaurant needed to get in touch with the Department of Sanitation to assist in garbage removal that was being impacted by construction, and we were able to help that business out. We also try to connect small businesses with key economic development groups to support their needs and concerns. When you do things like that, you can get the community behind you and your project.

How are different tunnel types (cut-and-cover, tunnel boring machines (TBM), Conventional tunneling, etc.) typically assessed and selected for an urban project? Are there any technological advances that are further impacting this element?

Barrie Roberts: The type of underground structure you’re going to build will go a long way to determining the means and methods used to build it. You need to consider the depth, size and complexity of the structure, as well as the ground and groundwater conditions that will be encountered. For example, TBMs may be ideal for constructing long transit tunnels through a variety of ground conditions but may not be the right choice for constructing a large profile station structure incorporating interconnecting entrances and ancillary system tunnels. In that case, depending on depth, conventional tunneling (SEM) or cut-and-cover methods are typically adopted for station construction such as those constructed in recent years for New York’s Second Avenue Subway and the No.7 Subway Line Extension projects. This does not preclude TBM tunnels from being used to partially excavate the station or being incorporated into a final station structure.

Harshad Pandit: However, there has been an advancement of some technologies, that now allow us to do things that could not have been done previously using conventional methods. For example, there are projects where we use ground freezing to improve soil conditions, which then lends itself to using a TBM or SEM method to tunnel. We have on-site instrumentation and software that lets us view conditions in real-time during construction so we can react and quickly mitigate any impacts to surface conditions or other nearby infrastructure. Even during the design phase, evolving software produces more accurate models and robust soil-structure interaction simulations that can inform a program early on. They’re also more user-friendly.

How has the increasing value placed on resilience (against flooding and other disasters) impacted urban tunneling?

Hamidreza Rezaei: Traditional tunnels were designed when storm and flooding events like Superstorm Sandy or Hurricane Harvey were rarer. Now that these events seem to happen more frequently, we have to adjust our approach during the design phase to account for these impacts and protect any underground structures or facilities like signal rooms. However, unlike surface infrastructure, tunnels that are designed and built properly from the beginning can last forever.

Harshad Pandit: Another factor driving the increased focus on resilience are the economic impacts of a transit system getting shut down due to a natural disaster. Whenever we have an event like Sandy or Hurricane Katrina, one of the top priorities is how quickly do we recover and bring people back into the city and give them a sense of normalcy. That’s why many owners who are building new underground infrastructure are looking at hardening methods early on during the design phase to plan for any kind of future event.

How are tunneling programs adapting to the increased desire to incorporate complex structures (i.e. stations, multi-layer track systems, etc.)?

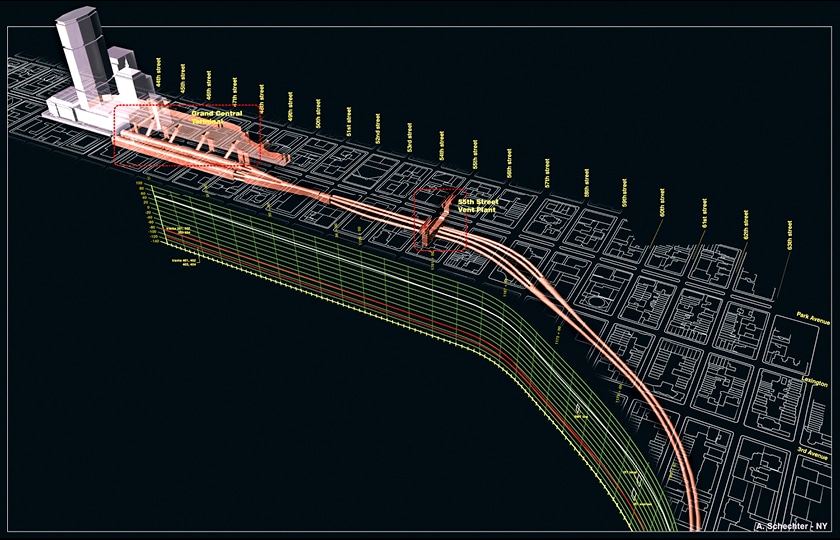

Jim Morrison: Our ability to put together a sophisticated design package has advanced so far compared to 10-20 years ago. We can now visualize urban areas in five dimensions or utilize technology like 3-D printing to create complex models that are then used to advance design and construction goals. The use of sophisticated design software such as 3-D numerical modeling, is a common part of any design that we deliver and is a very powerful toll to design complex underground structures Our team has the skill set to utilize these tools and we’re using them on most of the projects we’re involved with.

Barrie Roberts: Building Information Modeling (BIM) is used by multidisciplinary teams in planning, designing and constructing complex underground projects, like new transit systems. BIM allows accurate 3-D coordination and dimensioning of structures, spaces, systems, utilities, etc., thereby reducing the risk of defects or mistakes being discovered during construction. Design and contract documents are now incorporating BIM models rather than relying solely on 2-D design drawings.