To inform the design process of the Baltimore Therapeutic Treatment Center (BTTC), STV brought together global thought leaders in the medical, mental health, and corrections fields to engage in a series of knowledge-sharing sessions. In this three-part series, we explore the nuances of correctional design and its impact on those in contact with the justice system by sharing insights and knowledge gained from these sessions.

In part two of this series, we focus on understanding patient populations in correctional facilities to underline the importance of providing trauma-informed care. This piece features particular insights from Elizabeth Ford, MD, director of mental health and criminal justice initiatives at Columbia University Department of Psychiatry; and Erin Persky, Assoc. AIA, justice facility planner at Erin Persky & Associates LLC.

Trauma is exceedingly common among justice-involved individuals. Detained individuals increasingly present with histories of abuse, neglect, or violent experiences, often paired with psychological and medical concerns that may or may not be diagnosed. In addition, incarceration itself can be traumatic, lead to the onset of new trauma, and often retraumatize people in custody.

“The impact of one’s environment on their emotional state and behaviors is undeniable, just as is the impact of one’s ability to control that environment,” said Elizabeth Ford, MD, director of mental health and criminal justice initiatives at Columbia University Department of Psychiatry, and an independent consultant to STV for the BTTC project. “This is particularly true for environments of confinement, like carceral or involuntary treatment settings that are not chosen and from which one cannot escape.”

Regardless of architectural design, the state of being confined involves a loss of control, separation from normal life, exposure to strangers, and incredible uncertainty about one’s future and safety. These circumstances can elicit expected and “normal” reactions to confinement, which include irritability, agitation, aggression, despair, insomnia, hypervigilance, anxiety, panic, self-injury, violence, and more.

Architects need to be cognizant of these realities and think about how design can minimize these adverse effects. At STV, our aim is to reduce the fear and constant stress that a carceral environment can elicit, improve mental and physical health, improve behavior, and encourage more engagement in programs.

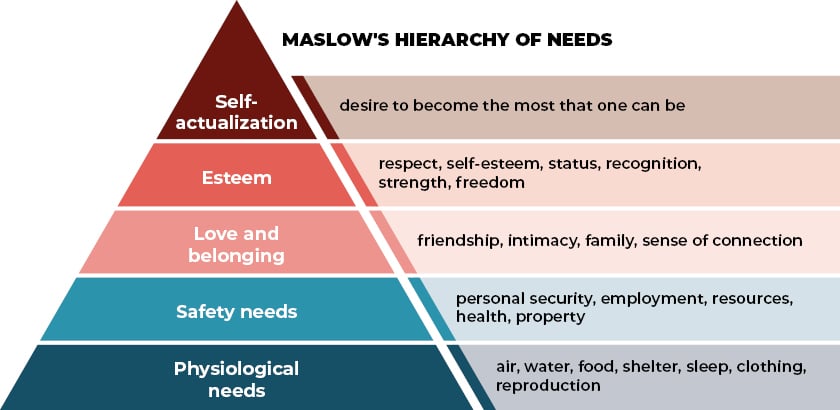

To achieve these goals, we must first understand the basic needs that we have to provide and support with our design to allow for healing. Based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, at the most basic level, we can help detainees meet their physiological and safety needs. Physiological needs include air, water, food, sleep, shelter, and clothing. Safety needs revolve around personal security, health, employment, property, as well as personal relationships.

Typically, detention facilities are not conducive to providing some of these most basic needs, including sleep and exercise, both of which are critically important for mental health. Through informed design decisions, we can provide spaces to better allow residents fulfill these needs. For instance, a tailored lighting intervention can result in improved sleep and reduced depression and agitation. Similarly, providing access to regular cardiovascular exercise through both indoor and outdoor spaces can promote mental health and sleep hygiene. Operational decisions regarding mealtimes, yard times, or patrol times have the potential to further enhance residents’ access to basic needs, supporting their mental health and well-being.

Like detainees, staff are highly susceptible to trauma – if not experienced in a significant way earlier in life, then often while on the job. By prioritizing their well-being and providing them with spaces that are bright and warm, and first and foremost safe, our goals for staff are to increase job satisfaction and decrease turnover, reduce stress and chronic fatigue, reduce errors while on the job, improve mental and physical health, provide a greater sense of control, and reduce the number and severity of injuries.

A trauma-informed approach to correctional design is critical to providing effective care for staff and patient populations in secure facilities. We should realize the widespread impact of trauma on individuals, recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma, respond to trauma in a sensitive and appropriate manner, and resist re-traumatization. These trauma-informed care principles, as outlined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, should be applied in all operational, clinical, and design decisions.

Understanding the trauma-informed approach as a context through which programming and design choices are implemented, our goal is to create spaces that support healing and well-being, promote a sense of normalcy, and allow residents and staff to thrive.

“It’s critical that we focus on how and why design decisions are made,” said Erin Persky, Assoc. AIA, justice facility planner at Erin Persky & Associates LLC, and an independent consultant who is collaborating with STV on the BTTC project. “A design can be beautiful but not necessarily trauma-informed. We have to make sure that the decisions we make are meaningful.”

The final part of this series will highlight specific design interventions and principles that we recommend based on the operational and patient needs that are presumed in a correctional environment.